Kildemock and it’s Jumping Church

Written by Rev Diarmuid MacIomhair – generously forwarded to this site by Leonard Hatrick

Part 1 - Background History

Kildemock is one of the countless little ruined churches all over the country. Embosomed in our green Irish fields, the graves of its dead around it, it is a quiet spot now, apart from the daily life of men. Yet it was not always like this. There was a time when it stood whole and entire under a roof of small medieval slates, its stone altar at the east end lighted by a stained-glass window, its threshold well worn by the feet of frequent worshippers. For it was a parish church, serving the people of ten townlands round about which constituted the parish, Paughanstown, Roestown, Hacklim, Millockstown (in which the church itself is), Hunterstown, Anaglog, Rathlust, Kilpatrick, Drakestown and Blakestown.

To find the origin of Kildemock we must go back a full fifteen hundred years, to the dawn of Christianity in Ireland. When Saint Patrick came here and converted the local chieftain and his people, he gave the care of the new flock to his disciples called Diomoc (pronounced Dom-ock), the same whose name survives also in Kildimo in County Limerick, in Kildeema in Clare, in Killeenadeema in Galway, and elsewhere. For their pastor the local people build a little church of wattle and clay, which they called by his name, Cill, or cell, of Diomoc, and which they afterwards replaced by a more permanent one in stone.

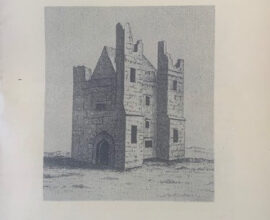

For many centuries church and parish had an uneventful existence. Then came the Anglo-Norman invasion. In 1189 the newcomers reached County Louth and in no time at all had settled in as undisputed masters. Alien as they were in many ways, these foreigners shared with their Irish subjects the common faith of Christendom. They too, were accustomed to build monasteries and endow churches. Sir Ralph Pipard, Lord of Ardee, was not behind his fellows in this respect, and when a monastery was built for the Knights Templars at Kilsaran, a few miles from here, he hastened to grant it the advowson of Kildemock. The effect of this was to entitle the Templars to all the revenue of the parish while leaving them the duty of providing a priest to minister to the people. That happened in the latter half of the thirteenth century and the arrangement continued until 1312, when the Order of the Knights Templars was suppressed and its property turned over to the brother Order of Knights Hospitallers of Saint John.

When Ardee sub-committee of the County Louth Archaeological Society excavated this site in 1953, they found fragments of stained glass and some carved stones which experts have dated approximately to the beginning of the fourteenth century. This suggests that what we see now is a re-building of the earlier church by the Hospitallers after they had taken it over. They may have changed the dedication also, because from this on we find the church called after Saint Catherin, the virgin and martyr of Alexandria, whose feast occurs on November the 25th.

Kildemock remained the property of the Knights Hospitallers for some two hundred and twenty-seven years. Then came the dissolution of monasteries by Henry VIII and further great changes in faith and worship known as the Protestant Reformation. For a long time these changes were little felt in country places. Everything went on much as it had always done. But eventually, from the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Crown began to enforce its religious policy in earnest and Catholic rites could no longer be used in the churches. As, however, the people remained Catholic, this meant that churches like ours were not frequented at all. The result was inevitable, and already in 1622 a Royal Visitation of Kildemock found “Church and Chauncell ruynous,” a state in which they have continued to the present day.

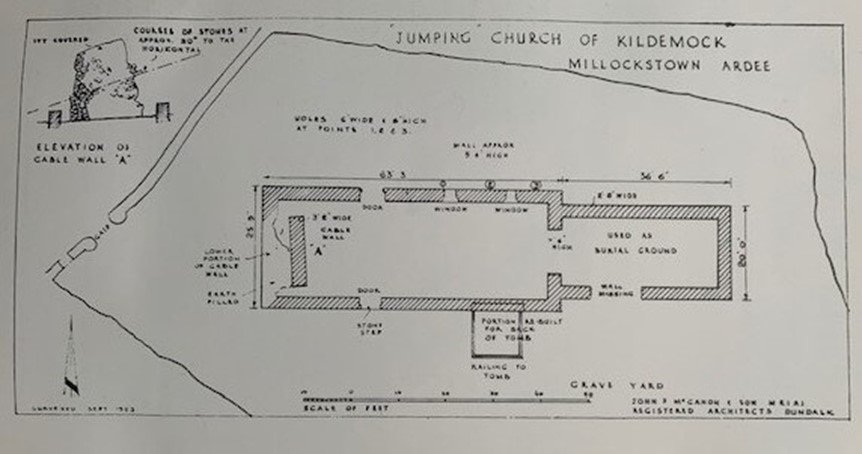

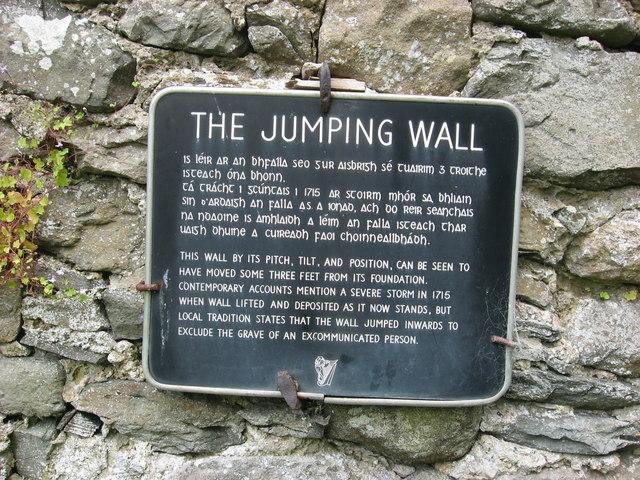

Part 2 - The Wall that Jumped

The story that a wall of Kildemock church jumped from its place has always been current in the neighbourhood, but until recently there was no observable evidence of this remarkable movement. Ivey, bushes, fallen stones, piled-up earth, all the accumulated debris of centuries, made it impossible to discern the true outline of the church. However, in 1953, as already mentioned, great improvements were effected by local archaeologists, generously assisted by An Bord Failte, and these have revealed the celebrated wall really standing two or three feet within its own foundation. There it is, nineteen feet high, fifteen wide and three thick, a mass of masonry calculated to weigh at least forty tons in its present state, rising from the bare earth close by the foundation from which it was clearly severed some three feet above the ground.

The evidence of our eyes is confirmed by adequate testimony from the past.

Dublin, March 29 1738-9

My Lord,

I had the honour of your Lo.ps. The affair of Molick’s Town Church near Ardee in the County of Louth is well attested by my brother and all the neighbours hereabouts who saw it before and after the storm.

I had the curiosity to go and see it myself and observed ye western Gabel end broke off, in a straight line, from its foundation, just above the ground, and placed perpendicular, about two feet forward in the body of the Church …”

(Copy of Mr D[obbs] the Surgeon’s letter to Bishop of Dromore, March 1738” among Harris MSS., in Armagh Library.

“Two miles from Atherdee are the ruins of Melickstown Church seated on a hill, remarkable for the effects of a violent tempestuous wind, the West Gable End of that Church was on Candlemas day 1715 moved by the storm two feet eastward and left standing within the walls, cut off in a straight line from the foundation which lay bare, and even a foot and a half above the ground to the Surprize of many curious and Creditable persons now living, who went to view it”

“In the Parish of Kildemock about one mile SE of Ardee by the W end of Millickstown church was forced in by a violent storm on a memorable day called Windy Candlemas about 29 or 30 years ago, the wall was torn from the surface about 6 feet equal on the NW side, the remainder of the wall that is standing is bout 2 feet and a half high at the Medium. The wall was broken off and shoved in 6 feet and an inch the height of that part of the gable that was forced in is about 16 feet and leans very much to the south, and is better than 3 feet thick. There was no Divine Service performed in the church at the time of this odd accident, neither is there any at this present, it is about 29 yards long and 7 wide in exterior measure. You may judge the cement must have been excellent, when the wall for the space of 6 feet equal with the surface was torn off on the NW side, and broke off about 2 feet and a half high from the level for some yards more on the SE when it was forced in so many feet from its original situation, when so many feet high, yet where in one entire solid mass, you may conceive say from these circumstances how incomparable the mortar as well as workmanship must have been there is no door in the W gable; a few stones of the small arch in which the bell formerly hung are yet standing upon the top of this forc’d in wall; the entrance into this church to the best of my recollection lyes on the S side. This strange accident was taken notice of by the news writers of those times, I had it well attested t omen by living authority, besides the first appearance of the fractured wall demonstrates a violent and unusual change in art effected by a natural cause. I carefully examined and measured the building, and was an eye-witness of what I relate.

From Humble and obliges Servt John Perry

Endorcement Jno Perry’s further remarks on some parts of ye County of Louth 1744” (Harris MSS, in Armagh Library)

- Millextown, Kildemock

“Melick’s Town, Bally Vellog, a farm house and a few cottages with the ruins of a small church not known to whom dedicated, a wonderful accident happened here which the inhabitants attribute to a miracle, in the great wind the beginning of February, 1715 the West end of the church which is about 6 yards broad and 9 high was by the wind lifted off the foundation and settled upright near 4 foot within the church, the belfry also was laid across the top of the wall whereon it was erected, it is at present in the same condition and near 3 feet of the wall whereon it stood is at present up.”

(Extracts from Isaac Butler’s Journal, 1744, in county Louth Archaeological Journal of 1922)

- 1820 volume II, page 91)

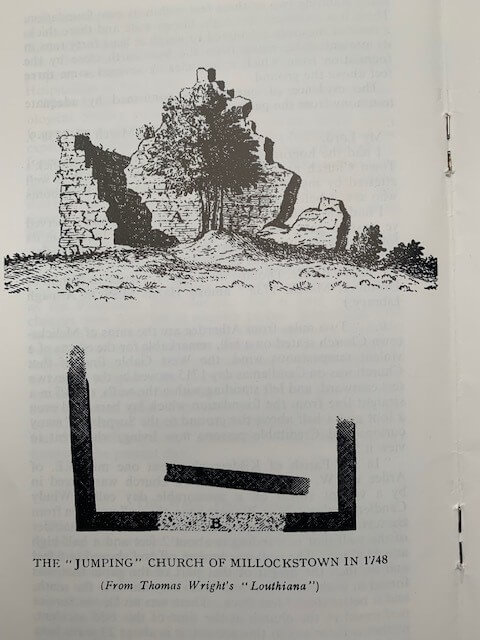

- “This is the view of the ruins of a church at Millextown near Atherdee, much resorted to upon account of the surprising position of the gable and A, which is confidently reported to have been blown away from its foundation B in violent storm and placed upright at C, where it now remains erect, which strange accident has no way as yet been accounted for in a satisfactory manner.”

(Louthiana, BY Thomas Wright published in 1748

- Three miles beyond Collon on the R is Millextown, the seat of Mr Orson. There is at this place a church, which greatly attracts the attention of the public, on account of the extraordinary position of one of the gable ends. Near Millextown is the glebe-houseof the Rev Dr Disney

- A church with an extraordinary position of one of the gable ends (Topography of Ireland by Sleator 1806, page 47.

- Millextown is on the right were is an ancient church the gable end of which standing at some distance is grevely reported to have been blown to the situation it now occupies in a gale ofwind (Excursions through Ireland, by Thomas Cromwell, 1820 volume II, page 91)

- In Millockstown TL are the ruins of an old church… The western gable partly stands declining towards the south. It has removed invward 2 years from its first foundation … The people say that a man who was excommunicated having died waws sby force of arms interred within this church immediately at the western gable and that the gable miraculously moved from its foundation so far inward as to leave the grave outside the walls of the church. The original foundation is to be seen 2 yards outside the gable, and over the grave (or where it is pointed out to have been) a tree stands to the outside of the gable. From this circumstance, it is commonly called the Jumping Church.

(Louth Ordnance Survey Letters 1835, published in County Louth Archaelogical Journal VIII (I) page 53)

All the evidence puts the reality of the jump beyond doubt. The careful statement of John Perry supported by IsaacButler also tells us how and when it happened. Since then new year did not then commence until March the 25th , the date assigned by Perry is, by modern reckoning, February the 2nd, 1716. As to the cause of the jump, we may perhaps wonder, with Thomas Wright, how a mere storm could achieve so violent and freakish a result. Storms flatten walls commonly enough; it is surely uniqute to find one neatly slicing off a wall, carrying it thgough the air, and setting it upright in a new position. To meet the difficulty there is a further supernatural explanation. Isaac Butler hints at it, and the Ordnance Survey Letter puts it into words. With the additional details furnished by oral tradition, the story goes as follows. – A certain man, a mason by trade, had abandoned the Catholic religion and turned Protestant. He was employed at the building of Stabannon church and on the 15th of August a holyday of obligation, when his fellow workers knocked off to attend Mass, he stayed behind. On their return, they found him lying dead at the foot of the scaffolding from which he had fallen. Attempts to bury the remains in various graveyeards having failed, for what reason is not clear, they were brough finally to Kildemock, and laid to rest along the west wall withing the ruined church. But the next day the wall was found to have jumped inward and left the unholy grave still outside the sacred enclosure. One version of the story adds that the corpse was then lifted and re-interred in an adjoining field.

This old and tenacious tradition cannot lightly be set aside, and we may safely take it there was such a burial as well as the storm. There remains the question how far each of these two occurrences was responsible for the result which we see. It is a difficult one. It leads, in fact, into a dark region where history has no more to say, and where it must be left to each on to formulate his own halting answer.

Part 3 - Other things of Interest in Kildemock cemetery

The oldest inscribed stone in the graveyard is a slab on the ground in the nave of the church, a memorial to the Orson family of Millockstown, who lived where you see a large house among trees on high ground to the south . The date is 1692.

A still older stone, without an inscription, is in the chancel along the north wall. It you look at it from a low angle you will notice upon it a faintly incised cross of rather beautiful design. The three upper arms each end in a trefoil or fleur-de-lis, while the slender, tapering stem passes through two knobs a little below the cross arm, and goes on to terminate in two moulded feet. Pattern and execution Pattern and execution are of the fourteenth – sixteenth centuries, while the position of the stone on the north side of the chancel suggests that it belonged to the most important family in the parish. This family might be the Dowdalls, who were in Millockstown from about 1500 to 1650, from whom Primate George Dowdall last holder of the individual primacy of Armagh is thought to have sprung.

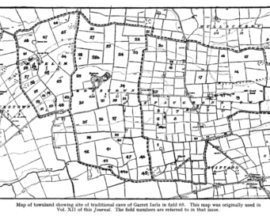

From where you stand in the chancel look north-east, in the direction of the blue Cooley hills. Four hundred years down the sloping fields, a low, irregular mound beside a hedge, is Garrett’s fort, where Gearoid Larla and his solders “lie asleep on horseback, their heads fallen down over their horses manes and their hands upon their swords. At the entrance of the cave hangs a sword and if a six fingered man should find the entrance and have the courage to draw the sword from the scabbard, the spell will be broken and the warriors will waken and ride out to battle.”

Towards the south side of the graveyard is the family headstone of the Boylan’s of Blakestown in this parish, which speaks of Michael Boylan who departed this life on the 22 of June, 1798 aged 26 years. With this colourless language it intimates the execution of young Boylan in Drogheda as a United Irishman and Leader of the Louth men in the Rebellion of 1798, a role, however which he unhappily failed to fill

Further particulars of Millockstown and its folklore, and the full story of Michael Boylan’s part in the ’98 Rebellion, will be found in an article in the County Louth Archaeological Journal, volume XII number 4. This article has also been published separately as a booklet. The annual Patron of Kildemock is held in the evening of June 24th, feast of John the Baptist.