Hacklim – Legend of the Sleeping Army

The townland of Hacklim lies to the south east of Ardee. This townland is on record from the early years of the Anglo-Norman occupation, which, over time had different spelling and pronounciation, including Heyghlem, Heglen and Heylem. The meaning of the name Hacklim, from the original Gaelic language, seems to be Each Léim, or Horse Leap. Hacklim runs across a ridge of land running east-west. Baltrasna sits to the north, with Millockstown to the south and Roestown to the east.

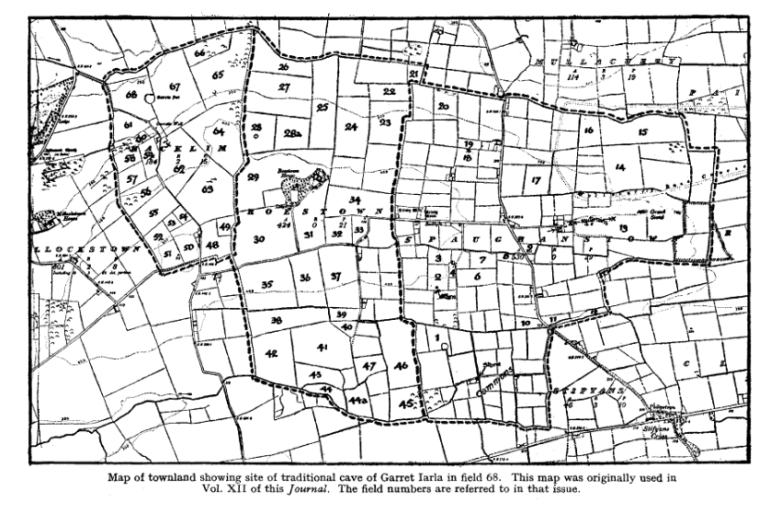

The fields 51 and 52 at the south west corner of the townland are known as Cly-airig and this is the area once known as Claidhe Ghearóid, Garrett’s ditch. On the roadside nearby lies a large stone called Garrett’s stone. Towards the other end of the townland, close by the ancient road, is Garrett’s well and a little further north, between two fields lies Garrett’s fort.

Legend of the Sleeping Army

The late Joseph Dolan of Ardee tried to find the chamber of cave that is supposed to exist below, but did not succeed. In 1929, Joseph Dolan published the following

“Garret Iarls, Garret the Earl (of Kildare). There is no record or tradition to connect the Fitzgeralds with ownership of the land in Co Louth. But legend assigns caves or forts in other parts of Ireland to the late Garett, Earl of Kildare, Silken Thomas’s father, for his sleep of enchantment with his troop of horsemen. The romance of Silken Thomas may have fostered the legend which identified his family with the enchanted warrior, who await the day to ride out for the last great fight of all to win Ireland’s freedom, and the belief in this warrior may be a memory of the tales of Angus Og and the other mighty lords invisible, who are to come thronging out of Brugh and join Lugh Lamb Fada in his triumphant return from Tir na n-Og.

The tale of Garret of Hacklim is that he and his soldiers are asleep on horseback, their heads fallen down over their horses’ manes and their hands upon their swords. At the entrance of the cave hangs a sword, and if a six fingered man should find the entrance and have courage to draw the sword from its scabbard, the spell will be broken and the warriors will waken and ride out to battle. Once a man found his way into the cave and took hold of the sword – as his raised it, the sleeping army gradually awakening, raised their heads from their horses necks and began to draw their swords. The man grew terrified and let drop the sword hilt, and as it slid back into its sheath, the soldiers heads fell down in sleep again and day for Irelands redemption was lost. “

Another account of the legend says that a member of the Earl of Kildare’s family, named Garrett, fought a battle against the O’Neills of the north in the townland. This account suggests that Garret and his men may have had their poetical existence in the shape of the harpers of Cooley, who came amongst the followers of Maebh on her journey to the Ford of Ferdia. This same account credits Fionn MacCumhail with having kept his castle at Hacklim.

All accounts discuss a cave which is beneath, or adjacent to, the rath known as Garrett’s fort and a person known as Gearóid Iarla and his troop of horsemen are in an enchanted sleep. They await the moment when a six fingered man will wake them by withdrawing a sword from its scabbard. Then they will come forth to fight for Ireland.

A Possible Explanation

One theory is that the Gearóid in the legend was a landlord in Hacklim. This was Garrett Colley. He lived in Ardee and he was portreeve of the town when the great rebellion broke out in 1641. Belonging to the Colleys of Castle Carbery, Co Kildare, he appears to have been the only catholic in his family; and in a mild way he supported the rebellion, thereby drawing upon himself the ruin of his house and his estates. These were circumstances calculated to enhance his memory among the people in the dark days to come.

Some time previous to 1641 he effected a mortgage up on his property, which is stated in a manuscript Court of Claims (1662-3) book in Armagh library in which Thomas Dowd declares the “town and land of Hayhlam in the barony of Ardee and one stone house in Ardee were mortgaged unto ye claimants father by Garett Cowly of Ardee before ye rebellion for £120.” By 1641 the Hacklim property had passed to Henry Cooly, who may have been his son, and was papist.

Let us suppose that Garrett Colley was a man of progressive ideas who took steps to improve his farms that he fenced the still unfenced medieval fields, built a mill and a house and even made a well. This would be an exceptional activity for that age, and might create the popular designations – claidhe Gheróid, muileann Ghearóid, teach, sgioból Gheróid, tobar Gheróid. These names would remain long after Garrett had faded from memory.

Cromwell

In the years that followed Garrett Colley’s tenure of Hacklim, the order of life in Ireland suffered a violent overthrow. The Cromwellian settlement and its later corollary of Williamite forfeitures swept the ancient families into oblivion and their place was taken by newcomers hostile to catholic faith and devoid of sympathy with native traditions.

Voiceless and powerless, they were driven in upon themselves with only their dreams to sustain them, dreams of a turn of the tide, of help from abroad, of the Stuarts or their own native chieftains back in power again. In this atmosphere it is easy to understand how Garrett Colley, who had left his name in Hacklim, would become the Gearóid Iarla of ancient Irish tradition, the supernatural hero who was to achieve his country’s deliverance. And, it is to this very period that the evidence points for the birth of the legend.

This is a possible conclusion to the ancient hero-tale of Hacklim by the imaginations of the Gaelic speaking fold of the early eighteenth century, because of certain memorials there of another Gearóid whose true identity had been forgotten.

And what of the cave? That there is a cave in Hacklim, as in the story, is likely to be true because caves or souterains are a common adjunct of rátha. If one should be found, we might find other explanations to the legend, as we have not a certain solution to date.

Excerpts taken from Jstor and the writings of Jospeh Dolan.