The Smarmore Slates

The article introduces the townland of Smarmore as set out in the paragraphs below. The description is still very much appropriate today. To help with the piece below, the East end of the church has a ‘Christmas Tree’ growing in it

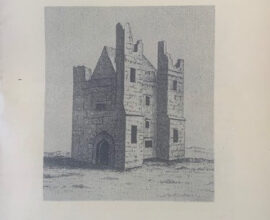

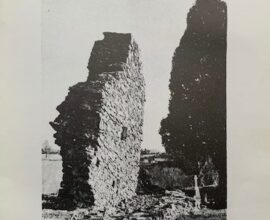

The village of Smarmore – it is scarcely larger than a hamlet – is in County Louth, some two miles South-West of Ardee. The ruins of the ancient church of Smarmore stand on a small eminence half a mile South-West of the crossroads which marks the center of the village, within the demesne of Smarmore Castle. The ruins are nowhere more than waist high, but the ground plan is clear. The church was very small, a little more than fifty feet long and less than twenty wide; near the West end a cross wall pierced with a narrow doorway marked off what may have been a porch; if this was the West door it cannot have been centrally placed, since the West wall is continuous from the South West Corner to a point North of the center line of the church. The nave is a plain rectangle and there is no trace of a chancel arch; there is a small aumbry in the South wall near the East end. Apart from the doorway in the cross wall and the two gaps in the North wall, the walls are continuous. The church is surrounded by a small graveyard, but there are no traces of any other buildings in the immediate vicinity; fragments of a ruined wall some distance to the West are probably unconnected to the church.

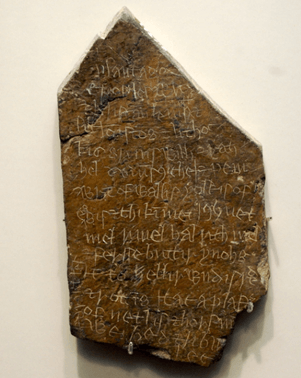

Until 1959 the ruins were covered with a mound of debris and earth, thickly overgrown with brushwood and small trees; during the summer of that year the Ardee sub committee of the County Louth Archaeological Society undertook the clearance of the site. The trees were felled and the brushwood cut down and the earth and rubble were removed until the original floor level of the church was reached; the spoil was thrown outside the church. When the clearance of the interior was nearly completed, it was noticed by two voluntary workers, that a number of fragments of slate in the heap of spoil bore inscriptions engraved with a sharp point. The spoil was carefully re-examined by the foreman and his assistant. As a result of their labours, forty-nine inscribed slates were recovered and placed in the National Museum of Ireland.

These paragraphs are the preamble to a detailed article investigating and attempting to decipher the mysterious Smarmore Slates

The cache is not in the grounds of the graveyard, but just outside. Although the area is quiet, it is well maintained and visited more often than the tranquility suggests so please be stealthy

A late 15th century inscribed slate was discovered at Smarmore church, Co. Louth in 1959 and is now on display at the National Museum of Ireland. It contains a medicinal recipe, most likely for a poultice, that would have been applied to an ulcer or wound to aid healing. The recipe uses a variety of wild herbs (listed below) as well as wheat meal, pig’s lard and butter to help bind the poultice together. The text is written in Hiberno-English/Middle English and contains at least two words that appear to have Irish/Gaelic origins. A number of other inscribed slates were also found at Smarmore, one of which contained a cure for horse aliments, so it’s possible that this recipe was intended for animal rather than human use.

This a version of the text using modern names for the various herbs

‘Weed plantain….. meadowsweet and leaves of silverweed (Irish word: briosclán) and butter and boiled ribwort plantain (lambs tongue) and little/some mallows (hocks) and groundsel and lousewort (rattle), swine grease/lard and wall pennywort, egg yolks, chickweed, wheat meal or rye-meal or similar meal and …butter… and two stems of red and rotting dwarf elder. Take a plaster of nettles (most likely the dead-nettle species), horse-mint, great plantain, ribwort and mistletoe (possibly from the Irish word: druadhlus)’ (after Britton & Fletcher, 1990)

Photos of a number of the plants used in the recipe are shown below, along with their medicinal properties according to various medieval texts. The majority of plants could be used to cure wounds and skin conditions, which would make sense if the Smarmore recipe was for a poultice

History of the Slates

It is unlikely there was ever a monastery at Smarmore. According to an extent made at Ardee on 30th September, 1540, the manor and rectory of Smarmore were impropriate to the Abbey of the Blessed Virgin, Navan,” That the manor and rectory were already impropriate to the Abbey before the coming of the Normans is made probable by the record of a lawsuit between the Abbot of Navan and the Prior of the Hospital of St, John of Ardee concerning the vill of Thurlesedeston (now Hurlstone) in the parish of Smarmore“

The subject-matter of the inscriptions on a number of the slates does suggest school use. On one face of No. 15, there is a simple sentence written in alternate phrases of Latin and English; that is, each phrase of the Latin is immediately glossed in English. The English phrases are underlined to distinguish them from the Latin, and there are several errors and miswritings. No. 29 is only partly legible, but it seems to consist of a string of useful Latin words and phrases.

No. 16 bears on one face a list of clerical titles and functions, and on the other a list of the liturgical hours and other olbots of the church; these might well form the basis of instruction on ecclesiastical organization.

Of special interest is No. 13. The two faces of which bear, in different handswriting, prayers for the soul of Jon Fir and Dai Daniel respectively.” The two prayers are nearly identical in form, and each ends with a prayer for’ all Christian souls,’ followed by “Pater Noster.’ Despite the difference of wording, these prayers are strongly reminiscent of the prayer still read from the pulpit for the commemoration of the dead: ” May their souls and the souls of all the faithful departed through the mercy of God rest in peace.’

One of the names, Jan Fit, is followed on its first appearance by the cognomen de Rabodi ; and it seems certain that Rabodi is identified with the townland of Rathbody, some four miles north of Ardee and less than seven miles from Smarmore. The local pronunciation of the name corresponds to the form Rabody which appears on seventeenth-century maps of Ireland.”

Taaffe family of Smarmore and Rathbody

It is probable that in the fifteenth century both Rathbody and Smarmore were already in the possession of the Taaffe family, though the evidence is unfortunately not conclusive. It is claimed that the Taaffes, formerly of Smarrnore Castle, were already in Smarrnore as early as 1320. They were certainly in Drakestown, half a mile from Smarmore, in 1384. The manor of Smarmore was granted to Sir William Taaffe by James I on 20th January, 1603, but this seems to have been no more than the confirmation of a long-standing tenure. In an unprinted Exchequer Inquisition of 1588 Nicholas Taafle is in possession of Rathbody and Arthurstown and there is mention of a John Taaffe of Arthurstown in 1630.

All the slates so far considered can best be interpreted as written in a school either by a master as a basis for instruction or by pupils as exercises; the variety of the hands and the nature of the subject matter suggest that the majority were written by pupils. They can hardly have been a monastic school proper at Smarmore, but there may have been a village school, organized by the curate of officiating canon. The existence of such village schools in the middle ages is well known.

Musical and Medical Slates

In any case, the scholastic slates are in a minority, and although the others may well have been inscribed by a schoolmaster-priest they seem to have no connection with school work

The non-‘ scholastic slates referred to are of two types: those containing medical prescriptions (mainly in English, but a few in Latin), and those inscribed with musical notation.

These latter (12,24,34,41) are particularly instructive. In the course of the middle ages, plainsong had developed through ure organum, in which the same melody is sung by two voices or choirs at an interval of a fourth or a fifth into polyphony proper, in which two or more different melodies are sung at the same time.

The medical prescriptions are likely to have been written by the schoolmaster-priest. The majority are in English, a few (19, 35, 37) in Latin. It would seem that the officiating priest acted not only as village schoolmaster but also as village doctor—and even, judging from No. 8b, as veterinary surgeon.

In view of the difficulty of transporting slates over long distances, the possibility that the priest brought them with him as a kind of medical textbook can be excluded.

There remain three other possibilities:

- the priest copied down the prescriptions from a borrowed manuscript; or

- he copied them down from some other source, possibly oral; or

- he made them up out of his own head and noted them down by way of memorandum.

The fact that No 8b1 the veterinary prescription, is in verse is some doubt on the third possibility: although it is certainly not impossible that the priest, having excogitated a useful veterinary remedy, should go to the trouble of formulating his memorandum. in verse, it cannot be said to be very likely.

The fact that the materia medica includes tropical substances which, although they were commonly used for medical purposes in the Middle Ages, would have to be imported casts doubt on the second possibility. Prescriptions obtained orally from local ‘ wise men or wise women would surely make use only of indigenous herbs. We are left with the first possibility, that the officiating priest had obtained a loan of a medical manuscript, and copied down on to slates those remedies which be thought likely to be most useful. If this hypothesis is correct it is of some interest to notice which ailments are prescribed for.

Both faces of No. 25 are concerned with cardiacle palpitations and with fever quartan, presumably some kind of malarial infection, On both Nos, 22 and 26 the obverse deals with some kind of flux or discharge and the reverse deals with purgacion to stomac or laxative for stomac.

No 35 (in Latin) is decipherable only in part, but it is concerned with podagra ‘gout’. The list is not very long: many of the prescriptions are not decipherable, and some of those which are, do not name the disease in question. Nevertheless, even if allowance is made for these qualifications, it is fair to say that the content of the prescriptions is considtent with the hypothesis that they represent the working notes of a village doctor.

With thanks to author Brendan Rogers for his inclusion The Smarmore Slates and Jstor. You can access the full account at Jstor here