The Grave of Ferdia

The Ford of Ferdia

By Joseph Dolan (Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Dec 1924)

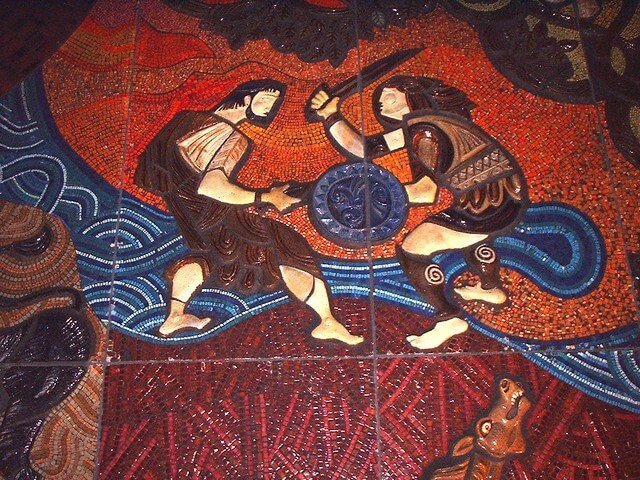

The fight of Cuchulain and Ferdia at the Ford, the most famous and most romantic episode in Irish legendary history, gives Ardee a unique interest. The identification of the actual site of the Ford – the place of combat – is therefore of importance.

The bridge over the Dee in the main street seems at first thought to be the spot where the Ford must have been. As the ford was the thoroughfare at which travellers crossed the river, roads must have come into use leading to and from it on each bank, and when in later times bridges were introduced, and a bridge was erected at Ardee to replace the ford, one would assume that the bridge would be built directly over the ford to connect the two existing roads and therefore that the bridge of Ardee which crosses the river in the main street would be the site of the Ford of Ferdia.

It would seem most unlikely that a bridge should be erected at another part of the river, away from, instead of at the ford which it was meant to replace, and that an artificial connection of new roads should be made to it and the old roads and thoroughfare at the Ford abandoned. Yet this is apparently what took place.

The Original Ford

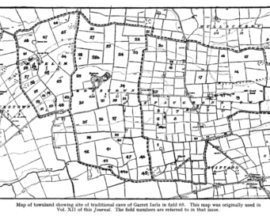

The original Ford of Ardee, the Ford of Ferdiad, was not at the bridge, but at the further or western end of St John Street, about 350 yards west up the river from the bridge, where the roadway (A) between the Workhouse garden wall and the Cloghen Bridge stream if continued as it formerly was, would meet the river at (F).

This is the local tradition,, saved for us by the Ordnance Survey letter writers of 1836, though all but lost by the next generation of townspeople – and confirmed by topographical evidence.

The choice of a different site for a bridge, away from the ford, may have been made to get advantage of high banks for its foundations. A ford where necessarily there were no river banks, and where the road sloped down to the water level would not supply any foundation for planks or masonry for a bridge. This might have caused the transfer of the thoroughfare to a more suitable site for a bridge.

The Ordnance Survey letters of Messrs. O’Keeffe and O’Connor, written at Ardee 27 January, 1936 and published in Louth Archaelogical Journal, 1922 runs as follows

Fionn MacCumhail

“Ardee town is called in Irish ‘Baile Ath Ferdiad, for which name the people account thus: Fionn MacCumhail they say, kept his castle at Hacklim (2 miles SE of Ardee). The Fear Dhiadh hearing of Fin’s fame came to challenge him to a single combat.” Then follows the common story of the giant’s being frightened away by the pretence of Fionn’s wife that her husband in the cradle was the child and that he could lift up the house in his arms and turn it round …. When he asked for a drink … “The woman told him that her men would not be content with any quantity of water that could be conveyed to the house, but went themselves to the At there below and satisfied themselves.

The Fear Dhiadh accordingly went, but as he was drinking, Fionn’s wife, by preternatural means sent an enchanted poisoned dart (Gae Bulga) after him, which despatched him on the spot. From this circumstance the ford was ever after called Ath Ferdiad, or the Ford of the Fear-dhiadh.”

The letter continues:-

“James Dolan, a native of Ardee, went with us to the Ford and pointed out where F-dh was killed and also his grave, which is about 14 yards long and about 9 or 10 feet broad, about 2 yards of the tumulus in the middle is cut away so as to be level with the ground – it lies immediately to the west of the river Dee about 80 perches west of Ardee.”

Dolan told the story of his death thus:-

“When the Fear-dhiadh flourished, Conchobher was King of Ulster; he lived near Armagh, his territory extending to near Drogheda. Conall-Cearnach was his grand master or defender of his territory, and Cuchullen was his lieut. Grand Master.

Cuchullen was at Castletown, called in Irish DunDealgan, near Dundalk, he encroached upon or did some injury to the territory of the Queen of Connaught, Medb and Cruachan, who employed Fear-dhiadh to revenge the injury upon him.

They met at the place now called Ath Ferdia, within 80 perches off Ardee to the west where an engagement took place between them. Cuchullen then gave Fear-dhiadh a mortal wound with the Gae bulga of which he immediately died: whence the ford is called Ath Ferdiad and the town Baile Ata Ferdiad.

Ordnance Survey

This measurement of distance, given by the Ordnance men is approximate enough to locate the site of the Ford, in conjunction with their note of its being in the townland of Area, and with one living man’s tradition of its site and with the undoubtedly reliable tradition of the late Mr James Halpenny, who lived the whole of a long life nearby, that the stage-coach used to cross the river at this spot not much earlier and perhaps even later than a hundred years ago.

“The place now called At Ferdiad within 80 perches off Ardee to the west.”

“It (Ferdiad’s grave) lies immediately to the west of the river Dee about 80 perches west of Ardee.

This, though accurate enough for identification is somewhat in excess of the actual length as scaled from the map, along the river or measured by chain by road which makes only about 350 yeards. I cannot suggest how to reconcile this overestimate with their meticulous detail on many subjects unless that “80 perches” was their pedantic way of saying a quarter of a mile, which would be a rough estimate of the distance.

In a later reference to the Ford (a week after on 3 Fed 1936) the Ordnance men say in enumerating the finds of antiquities in the district: “There does not agree with their earlier account of the distance but it is likely that only a rough location was given here, as distinct from the more accurate description needed in the accounts of the Ford itself.

Discovery of a Gold Ring

The report made to the Ordnance men of the finding of a gold ring at the Ford is another bit of evidence of its having being a place of recourse.

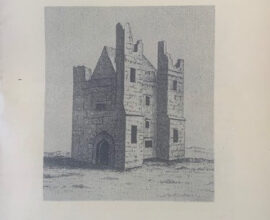

The statement that the reputed owner of the ring, Colonel Fleming, was one of Cromwell’s men is at variance with the well-preserved tradition that Fleming, a relation of the Lord of Slane, was the owner of Ardee Demesne castle and estate, and that Ruxton, his Cromwellian successor, lay in wait for him in the field on the north bank of the Ford or as another version told, half a mile further west at the field called the Big Borough – as he crossed the river, and there killed him and took forcible possession of his castle and lands.

This confusion of the Ferdiad legend with the later commonplace story of Fionn and the identification of Ferdiad with the giant must be a modern growth, or perhaps a graft made by some ill informed synthetic historian of the place. The gae bulga feature is evidently a literary interpolation.

Site of the Battle

The more or less correct version as told by James Dolan may only have been earned from books or from literary, not popular, local, tradition for the letter writers cite “the people” as the authority for the other tale. But it would seem likely that the name of Ferdiad and the tradition of his death in a combat at the Ford had lingered with the generations of the native Irish race who had held on here through Norman and Elizabethan and Cromwellian plantations, and that the site of the Ford remained of common knowledge, for the ford itself was not very long out of use in 1836.

The tradition perished altogether save with one man, within the last century. I would never find a trace of it or any knowledge of the names of Ferdiad or Cuchulain from any of the old people of Ardee who died within the last thirty five years. James Dolan who was able to show the Ordnance Survey men the grave of Ferdiad in 1836, though an old student who shared much of his lore with his nephew, my father, for twenty years later never told him of this legend or of the Grave. The only person living who ever learned any of it locally is Mr Patrick Byrne, who lives on the disused roadway to the Ford, and who heard from his predecessor, Owen McGeough, a man who would have been born over a hundred years ago, and from other old neighbours the story that two giants fought a battle in the field along the river under the Workhouse grounds, and that one of them was killed and was buried nearby.

As a matter of fact the actual field along the river at which the ford was, and in which the tradition stages the combat is immediately outside instead of within the eastern mearing of the townland of Areea or Ardee as defined by the Ordnance Map, but this seems an arbitrary or erroneous diversion of the boundary line from the stream which is the boundary to the point and which might naturally be taken as the boundary for the remainder of its straight course to the river.

Drogheda Old Road

But another verification of the site of the Ford is the fact that the old road from Drogheda and the south (B) – the only road till the construction of the present “Drogheda Road” or “New Road” (C) by the Speaker Foster, Chairman of the Grand Jury, about 125 years ago – reached the town at this point of St John Street (B), and that its direct continuation which was open in 1836 led straight to the Ford and most important of all is the statement of the late Mr James Halpenny, already referred to, that the stage-coach from Dublin to Derry, which came by this road from Drogheda, continued down the roadway (A) and crossed the river at the Ford (F) instead of turning up St John Street to the bridge, so that the ford was used contemporaneously with the bridge within the last hundred and fifty years, perhaps down to a hundred years ago.

No trace remains of the roadway which led from the Ford on the north bank of the river, it has been absorbed into the field.

The water is now deep and the banks a couple of feet high at the point where the Ford was, but this is due to the drainage operations and the straightening and diverting of the course of the river which were carried out in the first half of the nineteenth century – partly at least before the earliest Ordnance Maps (1836). The river bed was altered somewhat towards the north to straighten it a little west of the ford – some of its earlier course can still be traced in this field.

The bridge may have been erected at a different spot than the ford in order to get advantage of high banks for its foundations, as a ford when there were no banks and when the road sloped down to the water level would not supply any foundation for planks or masonry.

The Grave of Ferdiad

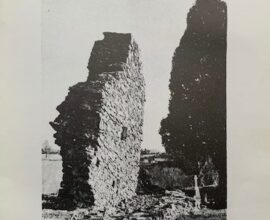

The disappearance of the grave of Ferdiad within the last 90 years is a most disappointing loss. There is not a trace, nor a tradition of the site, nor of its very existence left. From the Ordnance letters it must have been of remarkable appearance – 14 yards long, 9 or 10 feet broad.

Its location was evidently in the field at the Ford, between the workhouse and the river. “Dolan went with us to the Ford and pointed out where F-dh was killed and also his grave – it lies immediately to the west (must mean south) of the river Dee about 80 perches west of Ardee … “ They met at the place now called Ath Ferdiad within 80 perches off Ardee to the west”. There is the track of a stream bed in part of this field which is said to have been the former river course before the drainage operations. These alterations and cleaning of the river may have, probably, obliterated all trace of the grave after its having survived through the previous 1800 years.

The Legend of the Battle between Cuchulain and Ferdiad

Text Source:

Sigerson, George. Bards of the Gael and Gall: Examples of the Poetic Literature of Erinn.

“The warriors of Ulster are suffering from their annual debility,[*] and Cuchulain has been holding the whole army of Maeve at bay, single-handed, slaying a hundred men every night. After he has met the leading champions of Connaught in single combat, and slain the wizard Calatin and his twenty-nine sons, “who ran at him as one man, and put their twenty-nine right hands upon his head,” well nigh making an end of him, Maeve in despair urges his old comrade Ferdiad to go out and meet him, making him offers of great price, and, should he slay Cuchulain, her daughter Findabair, queen of the west of Elga. Ferdiad reluctantly consents, because his honour is at stake, and Maeve gives him her brooch with its hooked pin, as a guerdon [=reward].

Cuchulain is grieved to see Ferdiad coming out against him, and beseeches him not to fight, for he knows that Ferdiad must fall by his hand. He says to Ferdiad who is taunting him with cowardice: “When we were together with Scathach …. yon were my heart companion, you were my people, you were my family … I never found one that was dearer, it is sorrowful your death would be to me.” Ferdiad upbraids him, and Cuchulain ever reminds him of their ancient friendship. “We were heart companions, we were comrades in gatherings; we shared the one bed where we used to sleep sound sleep.”

Every day they come out and fight until evening, and when they leave off, each puts his arm round the other’s neck and gives him three kisses. Their horses are in the one enclosure, their chariot drivers at the one fire. Of every herb that is put to Cuchulain’s wounds, he sends an equal portion over the ford to Ferdiad, who in turn divides his food and drink with Cuchulain. The latter even is fretted when he sees a sad look on Ferdiad’s face on the morning of their second day’s fight, and laments that he should have come out to fight against his old comrade at the bidding of a woman. Ferdiad, conscious perhaps of his approaching end, answers, “O Cuchulain, giver of wounds, true hero, every man must come in the end to the sod, where his last grave shall be.” They renew the fight until the fall of evening, and it was “mournful, sorrowful, and downhearted, their parting that night.”

Ferdiad rises early on the morrow, for he knows that one or both must fall that day. He arrays himself in his battle suit, and dons his apron of purified iron, through dread of the Gae Bulg of Cuchulain. “He puts his crested helmet of battle on his head, on which were forty gems, carbuncles, in each division, and it was studded with shining rubies of the Eastern world.” They try the ford feat. Ferdiad has chosen it, though he knows that Cuchulain makes an end of every fighter that is against him in that feat. They fight from early dawn till mid-day. Cuchulain for the third time leaps up towards the “troubled clouds of the air,” and alights on the boss of Ferdiad’s shield, to strike at his head from above, and for the third time” is cast to the ground “as a light woman would cast her child.”

Cuchulain’s anger rises at this, and the flames of the hero-light begin to shine about his head. So close was their fight then that the “Bocanachs and Bananachs and the witches of the valley screamed from the rims of their shields, and from the handles of their spears.” The river is cast out of its course, so great is the fury of their fight. At length Cuchulain calls for his Gae Bulg, and the spear passes through the armour of Ferdiad and out through his body. “That is enough,” said Ferdiad, “I die by that. And I may say, indeed, you have left me sick after you, and it was not right that I should fall by your hand.” Cuchulain ran towards him and lifted him across the ford, so that his body should not be on the west with the men of Ireland.

Then a cloud and a weakness comes over him, and he begins to lament for Ferdiad, and to recall all their ancient deeds: “It was not right, you to fall by my hand; it was not a friendly ending. . . . O Ferdiad, it is a sorrowful story to me, that I should see you so red and so pale, I with my spear reddened, and you in a bed of blood, . . . Yesterday he was larger than a mountain; to-day there is nothing of him but a shadow.” The lamentations of these warriors and their queens are full of beauty and dignity. They are the crown of the tragedy, and almost justify it.”

CUCHULAINN LAMENTS FERDIAD.1

| Play was each, pleasure each, Till Ferdiad faced the beach; One had been our student life, One in strife of school our place, One our gentle teacher’s grace Loved o’er all and each. Play was each, pleasure each, Till Ferdiad faced the beach; One had been our wonted ways, One the praise for feat of fields, Scatach gave two victor shields Equal prize to each. Play was each, pleasure each, Till Ferdiad faced the beach; Dear that pillar of pure gold Who fell cold beside the ford. Hosts of heroes felt his sword First in battle’s breach. Play was each, pleasure each, Till Ferdiad faced the beach; Lion fiery, fierce, and bright, Wave whose might no thing withstands, Sweeping, with the shrinking sands, Horror o’er the beach. Play was each, pleasure each, Till Ferdiad faced the beach; Loved Ferdiad, dear to me: I shall dree his death for aye Yesterday a Mountain he,— But a Shade to-day. |

1. From the “Taín Bo Cuailgne.” In the Fight at the Ford, after mighty deeds, Ferdiad at last is slain. Cuchulainn, grievously wounded, bewails his friend. His charioteer at last beseeches him to leave; he consents, declaring that each contest and each combat which he had waged before was play and pleasure compared to this battle with Ferdiad. Then he speaks this lay. The original metre is reproduced. It will be observed that iterated or burthen lines appear in this poem, which was probably composed before the sixth century.