Bloody Sunday 1920 in Croke Park

ON THE MORNING of 21 November 1920, fourteen men lay dead across Dublin city after a synchronized IRA attack designed to cripple British intelligence services in Ireland.

Still thousands of people were on their way to watch the Gaelic football match between Dublin and Tipperary. Trucks of police and military rumbled through the streets, some of them headed for Croke Park. There was a sense of danger in the air.

Michael Foley recounts the extraordinary story of Bloody Sunday and the shooting in Croke Park that changed history forever. The following is an extract from his newly published book – ‘The Bloodied Field’.

MIDDAY

News of the killings reached Luke O’Toole at Croke Park early that morning as Central Council delegates from across the country gathered for a meeting to debate the rule banning GAA players also playing soccer and rugby.

O’Toole pulled aside Dan McCarthy, chairman of the Leinster Council, Jim Nowlan, Andy Harty, a Dublin GAA representative, and Jack Shouldice, Leinster Council secretary, an IRA veteran of the Rising and in charge of managing the gate receipts that day.

They all expected a reprisal. They knew Croke Park could be a target. Should they call the game off? Once again O’Toole duelled with the contradiction of what the GAA believed in private and how they wished to be seen in public: if the game was cancelled because of the killings, the GAA would be acknowledging the impact on their organisation of a violent, political act. That was an arena they didn’t wish to inhabit. They couldn’t call off the match.

Ticket Sellers

A crowd was already milling around outside. Ticket sellers were doing a brisk trade. The fruit sellers strolled along the road outside and around the pitch with baskets of apples and oranges. Hawkers sold badges and colours for the game. Before Tipperary footballers played Dublin that afternoon, Dunleary Commercials and Erin’s Hope were to replay their drawn Dublin county intermediate football final.

After completing his work at the Gresham Hotel, Paddy Moran had headed for Croke Park. As chairman of the Dunleary club, this Sunday had already meant a lot. The club was barely a year old and chasing their first ever title. He arrived in time to stand in for the team photograph, still wearing the broad, flat cap that had shielded his eyes that morning.

Dunleary had the breeze at the beginning. Two early goals got them seven points up at half time. Erin’s Hope charged at them in the second half, but their shooting was bad and Dunleary’s defence was good. Dunleary even scored another goal to win 3-2 to 0-2. Moran mingled with his team, then quietly disappeared into the crowd.

Other Squad members came to Croke Park with the same idea. Behind the goals on Hill 60, Tom Keogh stood with Joe Dolan and Dan McDonnell. Keogh had been in the party that killed Henry Angliss at Lower Mount Street. Keogh had even made a date with one of the maids before they left. Dolan and McDonnell could share their story of the burning room in Ranelagh Road, if not the woman scourged with a sword and scabbard.

McDonnell scanned the crowd. He was restless. He had little interest in football. Croke Park held even less attraction than usual for him this afternoon. Dolan was edgy, too. Vinny Byrne, who had led the attack in Upper Mount Street, had already mentioned to a couple of IRA men he thought the idea of going to Croke Park was madness. ‘Something might happen,’ he said. Just like Luke O’Toole, they all waited, and wondered.

2.30pm

Before the Tipperary team gathered at Barry’s hotel at lunchtime Tommy Ryan left Mick Hogan at Shanahan’s and went to Mount Street for a look. There was no sign of any shootings. The police had moved on. Every doorway looked untouched and undisturbed by violence.

He returned to Shanahan’s around eleven o’clock. There was a message waiting for him. It was Dan Breen. He was leaving for Tipperary as soon as he could. If Ryan wanted, he could join him. Staying around for a match and going to Croke Park, said the message, wasn’t a good idea. Ryan still decided to stay.

In Barry’s hotel, amid all the news brought to Dublin by visitors from Tipperary and the killings that morning, news also drifted around about the Tipperary team. Monsignor Maurice Browne and Mick Kerrigan stood in the foyer with their neighbour, Mick Hogan. They already knew Mikey Tobin was detained back in Grangemockler, nursing his sick father.

Kerrigan had been told to bring his shorts and boots just in case Tipperary lost any more players, but he wasn’t needed. Tipperary were missing a couple of players but the team still looked strong. Apart from Tobin, their great goalkeeper Arthur Carroll was replaced by Frank ‘Scout’ Butler from Mullinahone. Beyond that, it was a familiar-looking team. Mick Hogan, Ned O’Shea, Jerry Shelly were the full-back line in front of Butler.

Bill Ryan was in his usual position at right-half-back, alongside Jim Egan at centre-back and Tommy Powell at left-half-back. Tommy Ryan and Jim Ryan partnered each other at centrefield. Bill Barrett and Jimmy Doran were right and left-wing-forwards, flanking Jimmy McNamara, Glasgow Celtic’s old flame. Gus McCarthy started at right-corner-forward with Jack Kickham at full-forward and Jackie Brett in the other corner.

It wasn’t a team picked with another day in mind: there were no experiments, no gambles. This was the team that had brought Tipperary level in the pack with Dublin and within reach of an All-Ireland. They didn’t see this as an idle challenge match, filling a weekend before Christmas. Tipperary had travelled to make a point. They had come to win.

Browne checked the time. It was ticking quickly towards throw-in. They wished Hogan luck and edged through the thinning crowd in the foyer towards the door. Before he left, Browne looked around and saw footballers laughing and chatting with their neighbours and friends. Years later, this was how he would always remember them. ‘They were happy as sandboys,’ he wrote.

A few hundred yards away, across Mountjoy Square and down Fitzgibbon Street onto Jones’s Road, thousands of people now streamed into Croke Park. Three IRA men – Harry Colley, adjutant to the Dublin Brigade, Sean Russell and Tom Kilcoyne – slipped quickly through the cracks in the crowd. They were looking for Luke O’Toole. Word had reached Kilcoyne from a DMP sergeant that a force of Auxiliaries and military were being mobilised for Croke Park.

O’Toole met them with Jack Shouldice of the Leinster Council at the entrance gate by Hill 60. The IRA’s message was simple: call the game off. The men from the IRA’s Second Battalion, who usually stewarded these fundraising games, had already been pulled out.

The Auxiliaries and the military were heading for Croke Park. Close the gates now, Russell said. Stop any more people from entering. ‘Imagine if the machine guns open fire,’ he said. ‘What an appalling thing.’

It wasn’t that easy, replied O’Toole. Shouldice agreed. Put aside the politics, the difficulty now was in the timing. The game was due to start in fifteen minutes. What about the difficulty of moving so many people out of the ground now? Those who had already paid would probably want their money back.

Imagine the panic of a public announcement like this. The stampede to leave might lead to deaths all by itself. They also reminded the IRA men that the match was being played to raise money for a member of Second Battalion who had been injured in a fight while acting as a steward at Croke Park. That couldn’t be helped, replied Russell. Play the match at a later date.

The Dublin players were arriving while they spoke. O’Toole and Shouldice consulted again with Dan McCarthy, Shouldice’s colleague on the Leinster Council. As a compromise, O’Toole agreed to close the turnstiles to try and limit the crowd. As the IRA men walked down Clonliffe Road, Colley noticed the lack of stewards around the ground. Who would tell the turnstile men to stop allowing people in?

He nipped across to the stile at the corner of St James’s Avenue and told the turnstile operator there to close his gate. A few minutes passed. The crowd outside the entrance swelled and grew impatient. The turnstile man disappeared for a moment and returned in a temper, swearing at the IRA men. This was madness. He opened the turnstile and let the crowd in. Russell, Kilcoyne and Colley looked at each other. There was nothing they could do.

BILLY SCOTT peered out his living-room window on Fitzroy Avenue at the people strolling towards Croke Park. He was fourteen years old, with the greatest playground in the city at the end of the street. Wasn’t he lucky? Any day he liked he could stand on his front doorstep and see Croke Park. There was no tramping up from the dirty city below or sitting on trains coming from places far away.

Today he would eat his dinner before young Daly from a few doors up called in for him. They would go to the match and find a good spot, maybe in the trees at the corner of the pitch or along one of the high walls, or pressed down in the front row behind the fence at the canal end that separated the crowd from the pitch.

Dublin and Tipperary. There had been articles in the paper and great promises for the match.

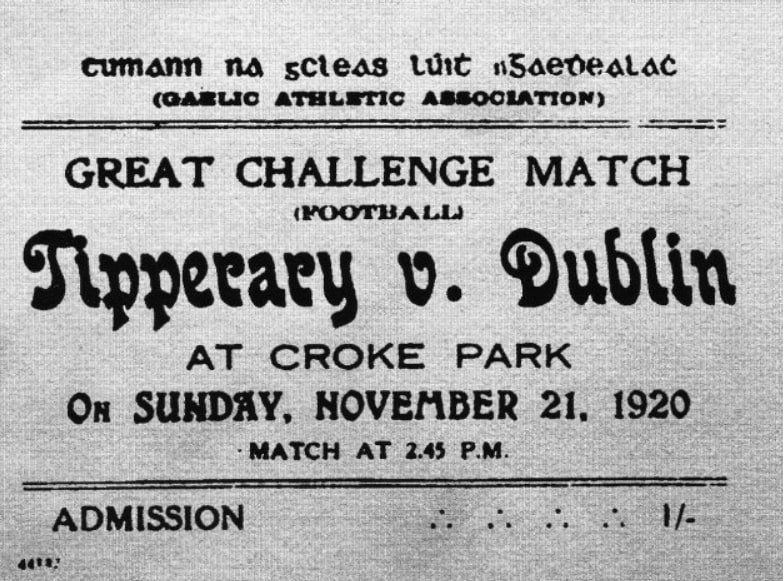

GAA Challenge Match

Tipperary (challengers) v Dublin (Leinster champions)

An All Ireland test!

At Croke Park tomorrow, 21st at 2.45pm

A thrilling game expected!

‘A good, scientific game should result,’ said the Sunday Independent. ‘Considerable interest is centred on the game. As Tipperary defeated the Metropolitans in their last two friendlies, it will be interesting to see, in view of future engagements, how they shape in the game under notice.

‘The Dublin team is just now in good fettle and they should prove a difficult lot to defeat on home ground. Tipperary have a good, strong, young team and as they were chief parties to the match they are certain to leave nothing undone to gain honours.’

When he came home from the match, Billy would have all the news for his father to take with him to work the following day. Billy could replay the game in school and the other boys would wish they had been there to see the Synnotts, the McDonnells and Frank Burke. Daly called and they walked together until they were lost in the milling crowd.

Up the road from Barry’s hotel in a small, shabby cottage down a muddy laneway, Michael Feery pulled a comb through his sandy brown hair. He did up his old army boots and buttoned a cardigan over his green undershirt. He was small and frail. His surviving front teeth were brown and rotted. All his years as a soldier, since before the war, had left him with few possessions and lots of time to sit on the kerb.

Home was the first damp, cold cottage in a row of seven on Gardiner Place, with his wife and son. They lived in perpetual hunger and penury, cheek by jowl with fine hotels and flea-bitten doss houses. The young shop apprentices employed by Clery’s department store were billeted around the corner. They had jobs and futures and a route away from Gardiner Place. On Sundays like this, Croke Park was Feery’s escape hatch.

It was the same for thousands of others. Down on Green Street in the tenements of the Ormond slum near Sackville Street, James Teehan from Tipperary wished his brother, John, good luck around half past two and closed the door of his pub behind him. He strolled past the ruins and tenements, smelling the freshly cut lumber stacked in the yard of Tickell’s timber store before striding out onto Sackville Street and up towards Croke Park.

William Robinson was eleven years old and lived on Little Britain Street, a few doors from Teehan’s pub. Everyone called him Perry. His father made a living as a labourer. Sometimes he bought and traded any spare stock he could get at the Ormond fruit market. Like his father, Perry possessed an eye for an opportunity. He knew Croke Park. He had a good spot in mind for this game, the crook of a tree at the corner of the canal end on the Jones’s Road side, looking across the pitch above the heads of everyone.

As throw-in time drew close, Daniel Byron and Jane Boyle found an equally good place on the halfway line across from the main stand. Perry Robinson was sitting in his tree. Billy Scott squeezed in among the men behind the Canal goal. Ten-year-old Jerome O’Leary, from Blessington Street near the Rotunda Hospital at the top of Sackville Street, was perched nearby on the back wall.

‘Ready’

The Dublin team were in their dressing room. Johnny McDonnell was there, his cap fixed. Ready. Tom Ennis, one of McDonnell’s comrades that morning on Upper Mount Street, slipped in the door, looking for Paddy McDonnell. They talked about the events of the morning and about the game being postponed. Paddy shrugged. The Dublin boys wanted to play. Twelve of the twenty players in the dressing room were O’Toole’s men. This was their home. Whatever came that afternoon they could take it, good or bad.

Frank Burke had seen O’Toole, Shouldice and the IRA leaders talking by the entrance gate as he arrived. He had set out that morning from St Enda’s school with his friend Brian Joyce and caught a tram to Parnell Square. Burke saw a newspaper placard and its headline about the killings. It was the first they had heard of it. He turned to Joyce. ‘There’ll be a raid some place today’. Croke Park never crossed his mind.

After leaving the Tipperary team in Barry’s, Monsignor Browne and Mick Kerrigan hurried along Mountjoy Square, down the hill past the Mountjoy brewery towards Croke Park. They were lucky. The crowds milling outside had forced a delay of the game. Instead of 2.45pm, the match would now start at 3.15pm. Even then, Browne and Kerrigan had barely slipped through the turnstiles and found a place on the sideline by the time the teams lined up.

Mick Hogan’s nerves hadn’t stopped twitching. He had asked Bill Ryan again in the dressing-room to change positions and spare him from Frank Burke, but Ryan grimaced. ‘It’s these boots,’ he explained. ‘They’re just too loose.’

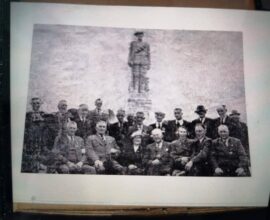

Hogan went to his bag and felt around inside, producing a spare lace for Ryan to tighten around his right boot. At least one of them could ease the other’s nerves. Everyone else seemed so calm as they jogged out onto the field. Jim Egan from Mullinahone was at the sideline talking to a priest from home, Fr Crotty. Some of the players even smiled for the team photograph. Hogan stood in the back row and sheepishly poked his head out between Bill Barrett and Jimmy McNamara.

‘Serious Business’

He jogged to his corner and waited for Frank Burke. The serious business of the day was upon him. No matter what way he tried to avoid it, Hogan would have to face Burke. Frank of the blistering dash and dancing feet. Frank, who could thread a kick through any gap you liked. Frank, who loved to score.

Then again, plenty had gone right this weekend. Hogan had survived a brush with the soldiers on the train and successfully delivered his message. He had seen something of the Monto on a Saturday night and successfully hidden his nerves from Monsignor Browne and Mick Kerrigan. Now he was in Croke Park on a bright November afternoon with neighbours and friends in the crowd and a great football match to play.

Whatever happened, he would have stories for Kate Browne and the boys by the fireside for the week and plenty to shorten the evenings between now and spring. If Frank Burke was the height of his problems, maybe they didn’t amount to much. Maybe everything would work out fine.

This article was taken from https://www.the42.ie/bloody-sunday-1920-1767626-Nov2014/